What Does Media Literacy Have To Do With The Holocaust? As it Happens: a lot.

by Frank W Baker (January 2023)

“The Holocaust never happened” Zack (a student) concluded in a paper he submitted to his teacher. Astonished, she asked, “Zack where did you get that information?” He told her it was from a reliable source—Arthur R. Butz, a university professor’s website. In the 1998 article “Teaching Zack to Think,” educational technologist Alan November

includes the URL (website address) that Zack provided his teacher: http://pubweb.northwestern.edu/~abutz/di/intro.html

When you look closely at that website address, you’ll notice a symbol that perhaps is unfamiliar: the tilde (~). It means a personal website. Alan November writes that if Zack had bothered to understand the URL and had taken the time to research Butz, he would have discovered that the author was a known Holocaust denier. (Source)

If students would take the time to deconstruct and analyze the URL, it would save them time. (How many bother to do that today?)

Skip ahead to December 2022: President Biden took to Twitter to declare that the Holocaust did happen and that Adolf Hitler was a demonic figure. He was speaking directly to those who had failed to condemn former President Trump (who had dined with a prominent Holocaust denier) and others who had used social media to promote

their antisemitism sentiments.

I’ve been teaching media literacy for more than 25 years. I have worked diligently to help teachers to teach their students “critical thinking” skills in order to help them formulate relevant questions about media messages. Mostly those messages come in the form of images and video, but today we cannot ignore the Internet and of course social media. It is social media, we must acknowledge, that receives the most attention by young people today. It is where they are getting most of their news and information.

What if that information is insufficient; biased, or simply wrong? What then? What happens if, and when, they find posts claiming the Holocaust never happened? Would they know how and where to seek out complete information; recognize the bias or locate appropriate, reliable sources? That is the challenge of the 21st century. Consider the following:

Almost 4,000 pieces of Holocaust denial and distortion were collected over two months in 2021, from five major online platforms: Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram and Telegram, according to a report released by the Department for Global Communications and UNESCO, in partnership with the World Jewish Congress.

Although most social media platforms have promised to remove such material, much of it remains.

“Understanding the history of the Holocaust is crucial to safeguarding our future,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres wrote recently. “If we fail to identify and confront the lies and inhumanity that fueled past atrocities, we are ill-prepared to prevent them in the future.”

Antisemitism has seen a dramatic rise in the United States. “According to the Anti-Defamation League, 2021 was the highest year on record for documented reports of harassment, vandalism and violence directed against Jews.” (Source)

In some ways, antisemitism in 2022 resembles the rhetoric of the 1930s. “At that time people like Henry Ford, Father Coughlin and Charles Lindburgh tried to blame Jews and frighten the rest of the public that the cause for the Depression and other problems in society rested with one group.” (Source) Coughlin’s weekly radio broadcasts reached an estimated 30 million listeners. (Source) Today, the Internet has the capability to reach millions in a matter of seconds.

“Antisemitism is a conspiracy theory” declared Deborah Lipstadt, the US envoy for monitoring and combating antisemitism. Students may already know that “conspiracy theories” (and those that spread them) are widespread today. But would they believe them when they see them, or question them?

I recently authored “We Survived The Holocaust The Bluma and Felix Goldberg Story,” a graphic novel detailing the true story of two Holocaust survivors. These two young Polish Jews recall how antisemitism overtook the townspeople who were formally their friends. As the Nazis closed in on their towns, and captured them, they were subjected to inhumane conditions. They both became slave laborers whose work helped the Nazi war machine.

The Research Process

In preparation for writing the book, I asked myself what I thought young readers would need to know. I also considered that teachers would use the book to meet Social Studies standards that include the Holocaust.

Research skills and media literacy questions became my guideposts. Where could I locate the information I was seeking; what Holocaust databases were available to me; how would I go about confirming and verifying important dates and other information?

Among other things, I located previously documented interviews with both of the Goldbergs. In most cases, when they mentioned specific towns in Poland or Germany, I wanted to know: where is this? My curiosity led me to use research skills and geographic maps to locate the towns. (Those maps feature prominently in our book.) When Felix Goldberg recounted that the camp he was a prisoner in had been bombed by the Americans, my co-author researched the event to learn that the camp had actually been bombed by the Soviets. Verification was important, because we wanted to be accurate.

Contemporary questions and seeking answers

If social media IS where most young people are getting information and news, it makes sense that today’s educators would need to include it in instruction. Alas, many schools ban it and teachers may not be familiar with how social media works, or why it has become so popular with their students.

What are the advantages AND disadvantages of using social media? Are students aware of its limitations? Do they always consider the source of what they consume? THAT is the quintessential media literacy concern- who is telling me this? Another important question that many don’t ask is “what is omitted and why”? Many social media posts are simply truncated, brief summaries that have been copied and pasted and forwarded. Some students may never seek out the full story or locate the original source material. Other posts include digitally manipulated images or deepfakes (videos), many of which are difficult if not impossible to verify.

No doubt, some students already know or are aware of the comments made by Ye (formally Kanye West), Whoopi Goldberg, and NBA player Kyle Irving. We might engage students in a discussion of where they heard it and what they heard. Was it a primary or secondary source? Why did these high-profile personalities say what they said? What were they trying to accomplish? Who reacted to it? And what did they say?

The Educator’s Role

In the graphic novel we’ve just authored, we thought it essential to introduce important vocabulary words and phrases and provide students with their definitions. This is an appropriate place to start with students. They may have heard certain words but not always understand their meanings.

Invariably students will have questions about the Holocaust, its causes and its aftermath. Fortunately, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has guidance for teachers in this area. See Frequently Asked Questions about the Holocaust for Educators

When educators decide which materials they’re going to use to teach students about the Holocaust, invariably many consider the strength (and weaknesses) of the that material, much of it media. (I recently wrote about the various ways teachers can use the media to insure their students are aware of the Holocaust.)

In a visual literacy workshop I conducted recently, teachers were presented with images from the Holocaust without captions. Using a worksheet, and critical viewing questions, they were encouraged to look for clues as to what was happening in the photo. The responses were revealing: they noticed things in the photos they might never have considered previously.

Many educators use the messaging by Nazis during WWII to introduce students to propaganda. A concerted effort

was made in the 1930s and 40s to portray Jews as money hungry, greedy, ugly and worthless. By spreading these kinds of posters, the messenger was able to reach and influence the masses.

A teacher using a documentary, for example, might consider if the film meets their teaching standards, goals and objectives. The teacher might even consider preparing students with pre-viewing questions like: does the producer have an agenda; is this balanced; who is interviewed (and who is not); are the images shown representative?

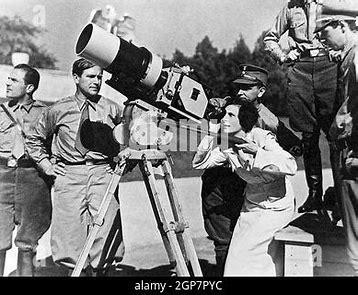

In “Triumph of the Will” documentarian Leni Risefenstahl pointed her camera up at her subject, Adolf Hitler.

Students who understand the “language of film” might recognize that this camera angle not only makes the subject appear larger, but also more powerful. Educators would be wise to help students understand: where you put the camera and how you position your subject implies meaning.

Your Librarian

I can think of no other person inside a school that can assist teachers more in the process of media and information literacy than your school librarian. If you’re reading this and don’t know how to start, I recommend your school library media specialist—credentialled and trained to help the teacher and the student. You cannot go wrong here.

Experts say the way to challenge the Holocaust denier is with evidence. Today, books, films, photos, testimonies and more are the primary sources educators should use to insure students have essential knowledge about the Holocaust. By insuring educators are properly trained in “media literacy” is also one of the most important steps we can take in a 21st century education.

Recommended resources

Nazi Propaganda and the Outbreak of World War II | by US Holocaust Museum | Memory & Action | Medium

Antisemitism Uncovered: A Guide to Old Myths in a New Era (adl.org)

Share This Page: