How To Get Started In Media Literacy Instruction

by Frank W Baker

I am often asked: how do I start to teach my students media literacy? The question reflects the fact that most teachers have not received sufficient instruction in order to begin addressing “critical thinking about media messages.”

Media literacy is more important than ever—now that we live in a world ripe with disinformation, conspiracy theory and more—all designed to fool unsuspecting people.

Media literacy at its core is about encouraging our students to question the media they come in contact with. That means everything from a meme, to a social media post, to YouTube videos, TikTok and beyond.

What is media? What is literacy?

I am surprised at how few students can define the words media and literacy. (So why not start here?) Then by combining the two words (media + literacy) it may give students a better understanding of what is meant by the phrase “media literacy.”

One of the earliest definitions of media literacy was to “access, analyze, evaluate, interpret and create communication in a variety of forms.” [See my previous post Students As Media Evaluators.]

A word that I am fond of, found in the Ontario Ministry of Education’s media literacy definition, is “techniques.” What techniques, we might ask students, are used to both attract attention and increase believability?

Every media text has an author and a purpose. I am fond of asking students, for example: “what is the purpose of television?” ( it’s not to entertain) and “what is the purpose of advertising?” ( it’s not to sell). [See What Do Want Students To Know About The Media.]

A teacher might invite students to bring into class a media example from their world. By asking them to do this demonstrates that a teacher values the media and popular culture of her students. In addition to examples from social media, students could also share a favorite TV series, film, video game or music artist.

Posting the common media literacy questions for all students to see is a good way to get them started down the road to becoming better critical thinkers. Students should have opportunities to ask and consider: who created the message; for what purpose; for which audience; what might be omitted (and why) and who benefits from the message. (There are many more questions of course.)

Consider the types of media that are used in instruction: everything from photos, to illustrations; videos and books. Once students get into the habit of asking those media literacy questions, that skill can transfer from their personal media favorites to their school media.

Visual Literacy: One of the most important skills

I am an advocate of helping students to hone their visual literacy skills using still images before teaching with about moving images (video and film.)

What does it mean when we say we want students to have visual literacy skills? In the art classroom this question appears to be central, but outside of art, I am not sure how often middle grades educators engage students in visual literacy skills. Yet, almost every book contains images; as do web pages, news feeds, and their social media accounts.

I have previously written about engaging them in “reading” photographs, for example. They are exposed to thousands of images but rarely do they conduct a “close read” of what they see. [See Teaching Kids To Read The Images They See. }

Engaging Students While Watching Video

Let’s admit here: most of us have never been taught HOW to watch television or film. That’s too bad because those media communicate as much, if not more so, than words on a page. So it stands to reason—if you’ve not received instruction on teaching media as text, you certainly couldn’t pass those skills onto your students.

One of THE most effective strategies when using video in instruction is to utilize “critical viewing skills”—how words and images work to imply meaning. One of the easiest ways to do this is to prepare a list of “pre-viewing questions”—what do you want students to know, notice and be aware of BEFORE they watch and listen? Next, an educator should also introduce and define vocabulary (or other words and phrases) that students are certain to encounter WHEN watching. Lastly, once the video has concluded, an educator should create and pose a list of “post-viewing questions” to make sure students understand everything AFTER they just experienced the video.

Viewing (as defined in the Canadian Common Curriculum framework) is ” an active process of attending and comprehending visual media, such as television, advertising images, films, diagrams, symbols, photographs, videos, drama, drawings, sculpture and paintings.” (Source)

Today we call this “active viewing” (as opposed to “passive viewing”) I have previously written about the importance of helping students understand “film as text.” If this is foreign territory to you, read my previous posts: “How to Close Read The Language of Film.”

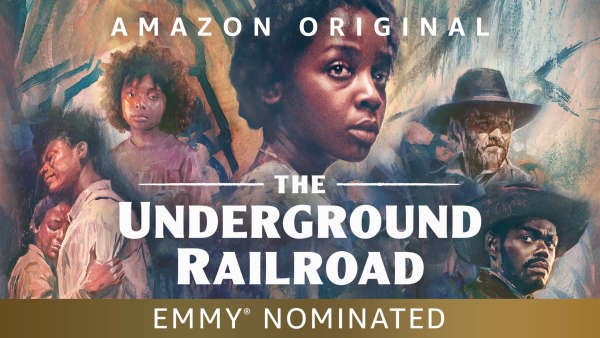

Let’s consider for example the recent Emmy-nominated series “Underground Railroad,” which aired on the AMAZON PRIME streaming network. “It tells the story of a young slave named Cora who escapes a plantation in Georgia and makes a long, arduous journey across several states while being pursued by a dogged slave catcher named Ridgeway.” (Source)

Unless prepared in advance, with some pre-viewing, media literacy questions, students may believe they are seeing true history on the screen.

Students watching this series could be challenged to identify what techniques the filmmakers used to make the film authentic. For example, costume, setting, music, etc.

Although the Underground Railroad actually existed, the story told in this series is fiction—some of which is based on historical events.

Adding to the confusion are those films which are heavily promoted as “Based On A True Story,” which again lulls viewers into thinking they’re seeing THE true story.

The Research Process

So I am a strong proponent of having your students conduct research to answer the questions: what was true and what was not in a film they may have been watching or assigned to watch.

Let’s not forget: engaging students in this process also meets the Common Core Standards: (Grade 7) “ Compare and contrast a written story, drama, or poem to its audio, filmed, staged, or multimedia version” and (Grade 8) “Analyze the extent to which a filmed or live production of a story or drama stays faithful to or departs from the text or script, evaluating the choices made by the director or actors.”

Share This Page: