| Key quote “It is no longer enough to simply read and write. Students must also become literate in the understanding of visual images. Our children must learn how to spot a stereotype, isolate a social cliché, and distinguish facts from propaganda, analysis from banter and important news from coverage.” Ernest Boyer, former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1988 |

In a world dominated by images and video, the ability to see through propaganda and understand the ever present slick marketing messages, is critically important. By some estimates, we are exposed to an average of three-thousand media messages everyday. Everyone, it seems, is out to sell us something. Today’s young people, exposed to thousands of media messages, don’t think critically about their media habits or consumption. They tend to believe everything they see, read and hear. If it’s on television, or the web, then (they’ve concluded) it must be true. Media illiteracy is rampant.

Communications scholar Marshall McLuhan observed that the fish, swimming in the ocean, is oblivious to the water. His metaphor is right: we live and swim in a world of media, but we seldom stop to study how the media work or think about its impact on our lives. Media literacy is designed to do just that and more.

I teach media literacy, one of the 21st century skills that all students need. By writing this book, I am hoping that you will consider its place in your classroom. But first you need to know what it is and why it is relevant to your students. If you teach with images, sounds or with videos, then this book is for you. In one of my recent workshops, I asked a large group of secondary social studies teachers if they could teach history without images, and they all said no. When I asked how many of them teach “visual literacy” not one person responded in the affirmative.

This book attempts to answer the questions: what is media literacy, why is it important and how might it be incorporated in your classroom. Although media literacy has been around since the 1970’s, many educators still don’t understand what it is and where it fits into the K-12 curriculum. The American education system has not yet fully embraced it. But, there are signs that this is changing.

In 1998, I created the Media Literacy Clearinghouse web site because I wanted to offer educators a one-stop venue for resources that would help them better understand media literacy and its place in the classroom. The center of the homepage is divided into three columns, each with background, readings, lesson plans and resources.

The left column contains some of the major media literacy concepts.

The center column is divided by curriculum areas.

The right column contains some of the more popular pages and resources that teachers have told me they like to use.

I hope you will take some time to explore the site. One word of advice: it is easy to get lost on a webpage with hundreds of embedded links.

Choose a topic (e.g. advertising) or a curriculum discipline (e.g. English) that interests you, and explore the resources on those pages.

In the hundreds of workshops I’ve conducted with teachers around the country, I take them through hands-on activities, designed to help them feel more comfortable teaching media literacy. Although I can’t do that here, I do offer a number of easy-to-incorporate ideas and lessons. Media literacy encourages us to consider the world of our students—their media; their popular culture—as the hook to get their attention and get them engaged, while also meeting those important teaching standards. On my website, you will find ideas for teaching with and about visual images, film, television, advertising and more. You will find topics as diverse as advertising, bias, journalism, news, parody, propaganda, and much, much more. I hope, after reading this book, and considering its recommendations, you might also feel more comfortable helping your students become critical thinkers and viewers in a 21st century world.

Media Literacy Defined

If we split the phrase “media literacy” apart, we come up with two words:

media (the plural form of medium)

literacy (the ability to read, write and comprehend).

We all know what the media is, especially our students. Literacy is one of the driving forces of education. We want students who can read, write, think critically and contribute to society.

In today’s education system, literacy is taught primarily through the printed word (books, magazines, etc.). Yet, media are also texts, designed to be read, analyzed, interpreted, deconstructed and created. Photographers, filmmakers, advertisers and other media makers know the languages and the rules which set media apart from the printed word–and it is these rules that media literacy aims to teach.

“If people aren’t taught the language of sounds and image,” says filmmaker George Lucas,” shouldn’t they be considered as illiterate as if they left college without being able to read and write?” 1

Simply put, media literacy is the ability to understand how the media work, how they convey meaning. Media literacy also involves critical thinking about the thousands of media messages we are bombarded with on a daily basis.

One of my favorite definitions of media literacy emanates from Canada:

“Media literacy is concerned with helping students develop an informed and critical understanding of the nature of mass media, the techniques used by them, and the impact of these techniques. More specifically, it is education that aims to increase the students’ understanding and enjoyment of how the media work, how they produce meaning, how they are organized, and how they construct reality. Media literacy also aims to provide students with the ability to create media products.” 2

Many educators know how to teach WITH the media; unfortunately, not many know how to teach ABOUT the media.

Media literacy is recognized as one of the 21st century skills all students need to succeed. The Partnership for 21st Century Skills (http://www.p21.org) defines media literacy as analysis and production.

Analyze Media

- – Understand both how and why media messages are constructed, and for what purposes

- – Examine how individuals interpret messages differently, how values and points of view are included or excluded, and how media can influence beliefs and behaviors

- – Apply a fundamental understanding of the ethical/legal issues surrounding the access and use of media

Create Media Products

- – Understand and utilize the most appropriate media creation tools, characteristics and conventions

- – Understand and effectively utilize the most appropriate expressions and interpretations in diverse, multi-cultural environments 3P21, working with teachers from all disciplines, has produced ICT (information, communication and technology) curriculum skills maps, all of which make specific recommendations to teachers who want to revise their instruction for the challenges of the 21st century. Included in each of these ICT maps is a page devoted to “media literacy.” To read the map for your discipline, go to http://www.p21.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&Itemid=33

The Importance of Analysis

Many teachers (and students) have become enamored of small camcorders because they are inexpensive and easy to use. They are increasingly being incorporated into instruction. While I applaud this move, learning how to use a camera, understanding editing techniques, and incorporating video into a project is only half of the equation. Students, in this example, are only creators and producers. Teachers should also be teaching their students how to analyze media productions. When we take time to help students analyze media messages, they learn to understand the underlying techniques that influence them everyday and they become healthy skeptics.

Writing in her book “Reading The Media In High School,” media scholar Renee Hobbs found that teaching students to analyze media messages also helped them become better readers of print material.

Pretty simply put, analysis combined with production translates to effective media literacy practice. Teachers who will teach it need to

engage their students in both activities. But media literacy is much more than just analysis and production, it is also:

– a set of skills, knowledge, & abilities

– an awareness of personal media habits

– an understanding of how media works (production; economics)

– an appreciation of media’s power/influence

– the ability to discern; critically question/view

– understanding how meaning is created in media

– healthy skepticism

– access to media

– ability to produce & create media

What media literacy is not:

– – media bashing: it is not designed to say media is bad

– – protection against media we might disagree with

– – just about television: in the 21st century it offers many opportunities to analyze and produce new media

and technology

– – just video production

– – how to use audio-visual equipment

– – only teaching with media; it is also teaching ABOUT the media

Media literacy is not a separate course; instead, it is lens though which we see and understand our media-saturated world. It is also a teaching strategy that should be incorporated into every course.

Whenever a teacher uses a photograph, a film clip, a commercial, an educational video, an audio recording, or a snippet from the news, they have an opportunity to engage students in better understanding:

-how that media message was created and constructed;

-who the intended audience is;

-what techniques might be used to engage, inform, persuade, educate;

-who or what might be omitted and why;

-who benefits/profits from the message being told in this way;

-what biases might be inherent;

-what stereotypes are promoted;

and more.

These, and other questions, are considered crucial to media literacy education. Questioning media messages, which many of us have not been trained to do, is one of the major strategies that can be employed in teaching with about the media.

Tessa Jolls, the President of The Center for Media Literacy agrees:

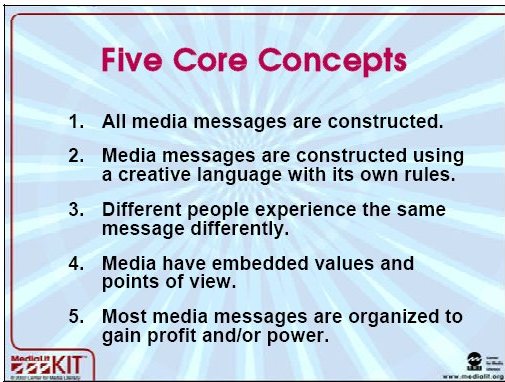

“It is our dream that by the time they graduate from high school, all students will be able to apply the Five Key Questions almost without thinking…Practicing and mastering the Five Key Questions leads to an adult understanding of how media are created, what their purposes are, and how to accept or reject their messages.”

The Center recommends students become familiar with the five core concepts as well as the corresponding critical thinking questions:

4

4

For a full explanation of the concepts and questions as well as examples, be sure to see the MediaLitKit, developed by the Center for Media Literacy.

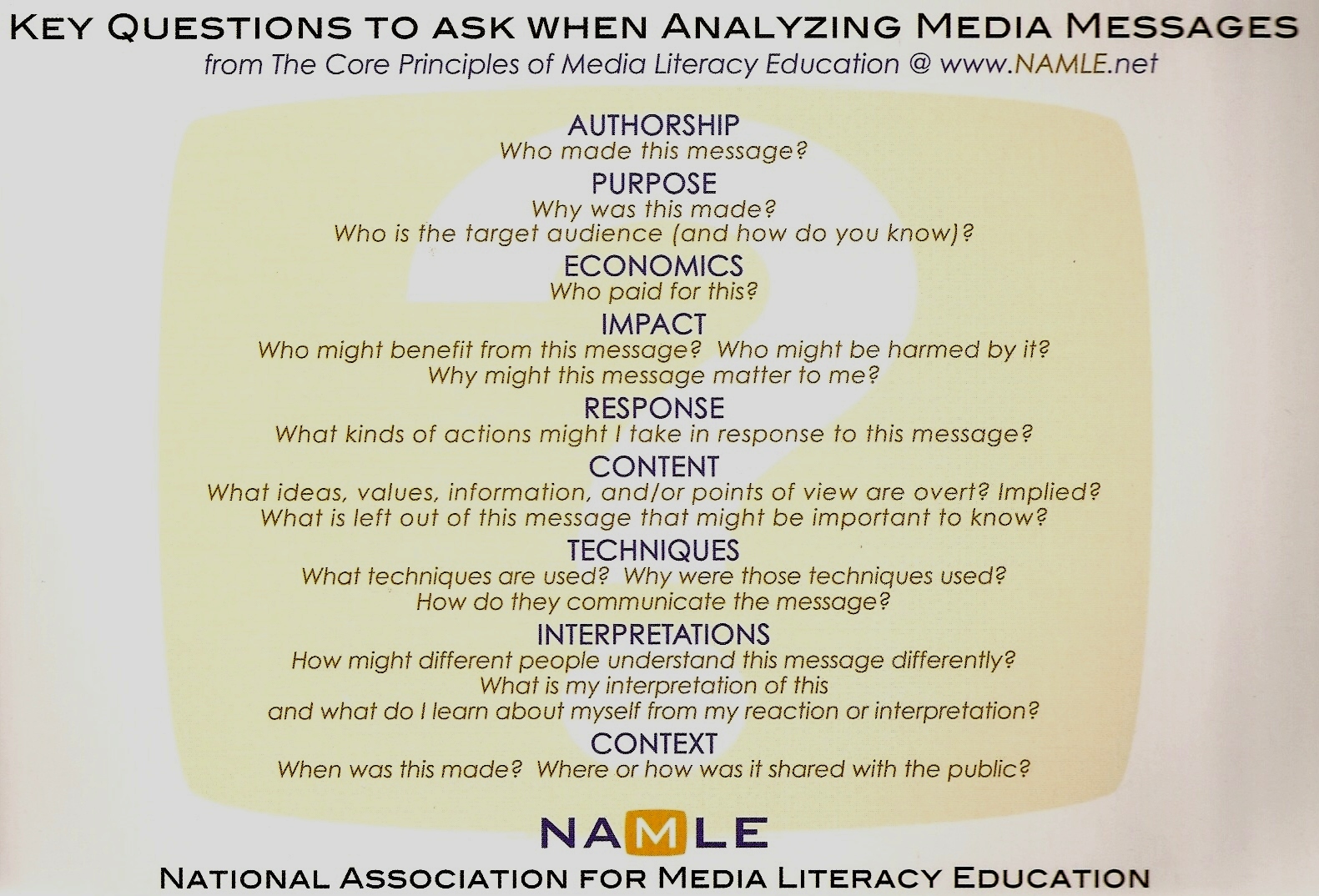

Meanwhile, The National Association of Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) recently recommended this longer list of questions for all students to use when considering media messages:

Source: NAMLE handout

NAMLE hopes that you will download the questions, produced as a handy one-page handout on this page,

(http://namle.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/NAMLEKeyQuestions0708.pdf)

post them in your classroom, project them on a SmartBoard or overhead projector and use them every time you teach a media literacy lesson. The more you use them, the more familiar your students will be with questioning media messages, whether they emanate from television, Google, or Twitter.

Media Literacy & Curriculum Standards/Disciplines

In 1998, while attending a National Media Literacy Conference, I was struck with an idea. If we want young people to become media literate, perhaps we should examine each state’s curriculum standards and look for evidence of it. That’s exactly what I did. Working with Rutgers University media professor Robert Kubey, we decided to concentrate our media literacy search in three major curriculum areas: English/Language Arts, Social Studies, and Health.

The results of our study (published in October 1999 in the trade publication Education Week) surprised us and most of those working in the field of media literacy: elements of media literacy could be found in almost every state’s standards. The phrase “media literacy” is not often used, but when we examine those three disciplines, it becomes clear that certain words and phrases are common to almost all of the state’s standards.

For example, in English language arts, there is the phrase “non-print” texts: this refers to television, radio, motion pictures and more. In addition, “persuasive techniques” is included in most ELA standards (and examining advertising and commercials is one way of using the media to teach students how to identify those techniques.) Bias is also taught in ELA classrooms when students study “author’s bias,” but also media bias. Many teachers who use film are helping their students understand narrative structure, symbolism, camera angles, and more. (The National Council of Teachers of English has consistently recommended media literacy education. Resolutions and position statements, some dating back to the 1970s, have recognized the power and influence of media texts on young readers. Many state’s revised their ELA standards based on NCTE’s recommendations.)

Writing in “The English Teacher’s Companion” author Jim Burke urges English teachers to embrace media when he says: “Movies, advertisements, and all other visual media are tools teachers need to use and media we must master if we are to maintain our credibility in the coming years.” 5

States, like Texas, have made media literacy part of the Reading standard:

“Students use comprehension skills to analyze how words, images, graphics, and sounds work together in various forms to impact

meaning.”

In 5th grade, Students are expected to:

(A) explain how messages conveyed in various forms of media are presented differently (e.g., documentaries, online

information, televised news);

(B) consider the difference in techniques used in media (e.g., commercials, documentaries, news);

(C) identify the point of view of media presentations;

(D) analyze various digital media venues for levels of formality and informality.

In Connecticut, the ELA standards say:

6th grade . Evaluate the credibility, accuracy and bias of informational text, including Internet sites, electronic recordings, visuals and other

technology resources.

7th grade Evaluate how authors, illustrators and filmmakers express political and social issues.

In Social Studies, many states refer to the rise of mass media (radio, TV, film) in American history. Propaganda is also commonly found in many history standards. The role of the media in the political campaign process is another way teachers can address media literacy, by studying how candidates use the media to teach citizens, especially during the election time of year.

In 2009, the National Council of the Social Studies (NCSS) approved a position statement on the importance of media literacy. It says:

“Media literacy is a pedagogical approach promoting the use of diverse types of media and information communication technology (from crayons to webcams) to question the roles of media and society and the multiple meanings of all types of messages. Analysis of media content is combined with inquiry into the medium. This approach is analytical and skill-based. Thus media literacy integrates the process of critical inquiry with the creation of media as students examine, create, and disseminate their own alternative images, sounds, and thoughts.” 6

In Health, the media is specifically referenced in the National Health Education Standards:

“Students will analyze the influence of family, peers, culture, media, technology, and other factors on health behaviors.” 7

Examples from the states:

In the state of Colorado, the health standard for middle and high school says: “students should be able to identify and explain how the media may influence behaviors and decisions.”

In South Carolina, high school students “examine ways that media messages and marketing techniques influence alcohol, tobacco and other drug use.”

The state of Georgia’s standard says students will: “identify ways various forms of media, such as movies, glorify drug use.”

And in Missouri, the standard reads students will: “evaluate the idealized body image and elite performance levels portrayed by the media and determine the influence of a young adult’s self concept, goal setting and health decisions”

Other Disciplines

Some of the same concepts of media literacy are also covered in many of our arts classrooms, where students begin to appreciate the techniques used to create productions. Understanding “visual literacy” by studying painting, for example, is a skill which can transfer to the analysis of still images such as photographs, posters

and other visual representations.

Media literacy is also a fixture in many other disciplines….even though it is not referred to as such. In science classrooms, the centerpiece is on inquiry: asking questions. More recently, there has been a push to increase the “science literacy” of students and the general public. Many science teachers use videos to teach complex topics; others use popular films as examples of addressing biology, space science, astronomy, chemistry and physics.

Every time an educator uses a video with students, they have yet another opportunity to engage them in critical thinking and viewing.

In math classrooms, teachers could (and should) expose students to the manner in which the news uses numbers, and the graphical representation of numbers. Key media literacy concepts (explored further in the next chapter)

are great ways to get students thinking about how numbers are used by news writers and reporters.

Why Teach Media Literacy?

I have described media literacy as a lens through which we see and understand our world. Media literate educated people are more likely to see through propaganda, question marketing, understand stereotypes and be able to identify their own biases as well as those of authors. Without media literacy, more people will be fooled because they don’t understand how they’re being manipulated. Here are a few more reasons why media literacy

is important:

Today, more attention than ever is being given to the amount of time young people spend in front of the screens (TV, computer, etc.) Research tells us that the more time young people spend watching television, the worse their grades are. That’s not all: increasing screen time has also been linked to junk food consumption, obesity, attention deficit disorder and a host of other health effects. Pediatricians are now asking parents about their children’s media habits, just as they would ask about the food they eat and the liquids they drink.

Every holiday season, millions of Americans head to toy stores to buy toys. Their toys purchases are often based on toys advertised on television, and because the majority of these young people have never had any media literacy education, they’re not able to see through the deceptive and manipulative practices of commercial producers that make toys look better than they really are. (More about toy advertising and what teachers can

do later in this book).

Every four years, millions of us go to the voting booths and elect the next President of the United States. More than likely, we will have seen on television and online, one of the candidate’s commercials, (created by slick Madison Avenue advertising executives), designed to make us feel good about the candidate. These are the same people who sell us toothpaste. Without a media literacy education, we might elect someone based on their looks and the production values of a 30 second commercial. (The White House has its own propaganda-producing unit, known as the Office of Communications.)

Large and influential corporations maintain public relations and marketing staffs ready to go to work at a moment’s notice if and when needed. Media observer Jean Kilbourne notes: “Huge and powerful industries—alcohol, tobacco, junk food, diet, guns— depend upon a media-illiterate population.” And she adds, “using the tools of media education (that) enable us to understand, analyze, interpret, (to) expose hidden agendas and manipulation. ” 8 It’s critically important for young people today to know who creates these slick messages and to be able to see through their creative and persuasive techniques.

Product placement describes the multi-million dollar practice of placing real products inside the plot of prime time television shows and popular motion pictures. Why is this happening? More of us are “zapping” the commercials with our DVRs and TIVOs. Advertisers know that audiences aren’t watching the ads, so their answer is to put the products inside the shows, where we will be sure to see them.

In 2010, the MacArthur Foundation released “Kids and Credibility” a major report examining young people’s use and understanding of information found on the Internet. It was widely believed, but not yet proven, that students, who use the Internet for their homework and other research, believe the web to be today’s encyclopedia—containing all of the information (and answers) to questions they might need for school and beyond.

The “Kids and Credibility” report confirmed our worst fears. The survey, of young people aged 11-18, revealed

that, among other things, “89 percent believe that ‘some’ to ‘a lot’ of (what is online) is believable.” 9

Full report available at: http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/full_pdfs/Kids_and_Credibility.pdf

The Benefits of Media Literacy Education

The Center for Media Literacy says teaching media literacy skills to young people helps them acquire an empowering set of navigational skills that include the ability to:

– access information from a variety of sources

– analyze and explore how messages are constructed, whether print, verbal, visual or multimedia

– evaluate media’s explicit and implicit messages against one’s own ethical, moral, and /or democratic principles

– express or create their own messages using a variety of media tools 10

The College Board’s Standards for Student Success, in its Standards for English and Language Arts, also identifies what it means for students to be media literate:

1. Students who are media literate communicators demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the ways people use media in their personal and public lives.

- Media literate students know and understand the complex relationships among audiences and media content.

- Media literate students know and understand that media content is produced within social and cultural contexts.

- Media literate students know and understand the commercial nature of media and demonstrate the ability to use media to communicate to specific audiences.

- Media literate students understand, interpret, analyze, and evaluate media communication.

- Media literate students use a variety of technological and informational resources (e.g.,libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- Media literate students understand, interpret, analyze, and evaluate media communication. 11For all of these reasons, and more, media literacy education is vitally important. It equips young people with the skills they need not only to question media messages, but also to be critical and competent communicators and producers in a 21st century.

———————————————————————————————————————

1. Life on The Screen: Visual Literacy in Education, http://www.edutopia.org/life-screen

2. Media Literacy Resource Guide, Ministry of Education Ontario, 1997

3. http://www.p21.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=349&Itemid=120

4. pg 17 http://www.medialit.org/sites/default/files/01_MLKorientation.pdf

5. Burke, Jim, The English Teachers Companion (3rd Ed), Heinemann; 2007 Chapter 13 Media Literacy, page 341

6. http://www.socialstudies.org/positions/medialiteracy

7. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sher/standards/

8. pg 305, Can’t Buy My Love, How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel, Jean Kilbourne

9. http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=12287

10. Arts Education Policy Review Vol 107, No. 1, September/October 2005

11. page 55, The College Board English Language Arts Framework, http://www.collegeboard.com/prod_downloads/about/association/academic/EnglishFramework.pdf