How To Read A Political Ad (revised, 2024)

How to Read A Political Ad: (revised)

by Frank W Baker (2024)

For years I’ve been interested in, and have followed the development of, political campaign commercials, especially around election time. They are seemingly all over the airwaves. You can’t get away from them it seems.

I even wrote a book about them and created a website for educators.

With some background knowledge, I’ve frequently taken this topic to social studies educators. I always wanted to share with teachers what I know; provide them with some useful resources; and help make them feel comfortable using these ads in their classrooms.

The most important question I ask myself is: what do educators and students (my audience) know (AND what do I want them to know) about these slickly- produced, influential messages?

The problem arises in that most of the commercials are 30 seconds in length, and they go by so quickly, we don’t really stop to think about HOW they were made and WHAT TECHNIQUES they use to be effective. In addition, many of us are not trained in how to think or view critically. That’s where media literacy comes into play.

Media literacy, which I’ve been teaching for more than 25 years, implies that the viewer questions and sees through those techniques enough to understand how they evoke emotion and get us to vote for a person or support a cause.

When Barack Obama first ran for President, his initial commercial portrayed him relaxed, sitting in a living room, speaking directly to the camera, while soft guitar music was heard strumming in the background. (See that ad here).

Later than evening, Comedy Central comedian Jon Stewart poked fun at the ad, nothing that anything would sound good with light guitar playing in the background. So he proceeded to read attributes of Mad Cow disease, while guitar music played. His audience roared with laughter. But I found Stewart’s joke to be at the heart of media literacy- how music, even subtle as it is, is a way of making the audience feel comfortable with the message and the messenger.

AUDIO + VIDEO

Educators can access a candidate’s ads on their websites and typically on any one of the streaming services such as YouTube, Vimeo and the like. One of the advantages here is you can pause the ad and call student attention to one or more aspects. So what am I referring to?

Consider:

– how the candidate is dressed; expressions or gestures

– the location

– symbols used

– the diversity of people represented (or underrepresented)

– music or other sound effects

– words on the screen (e.g. candidate’s name, party affiliation, website or QR code)

– the disclaimer (I’m ____and I approve this message)

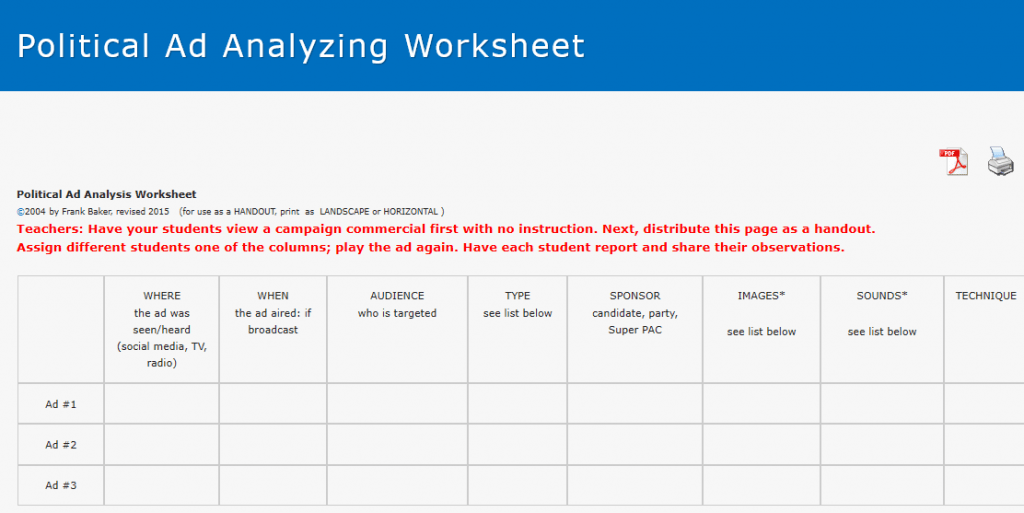

See also my printable Political Ad Analyzing Worksheet.

It’s not only the candidates who are buying time; it’s also a large number of Super Pacs. The Open Secrets website identifies these organizations and how much money they have raised. Frequently they support one candidate, but by law are prevented from coordinating with that candidate. (Read more about the history of the Super Pacs here.)

Techniques of Persuasion (aka propaganda techniques)

I think it will be critical for students to be able to recognize and identify the specific propaganda technique being used in these ads. (Unfortunately, techniques have been omitted from the current COMMON CORE ELA STANDARDS in favor of argument.) Nonetheless, innovative educators can still help students in this regard.

Here are some of the most common:

Testimonial: Using well-known or credible figures to influence the target audience.

Stereotyping: Highlighting stereotypes and either reinforcing or shattering them with the message.

Fear appeals: Creating fear to sway public opinion.

Bandwagon: Encouraging people to follow the crowd.

Plain folks: Creating a likeness of the candidate to the average voter.

Transfer: Using popular symbols to create a positive connection.

Name-calling: Using negative language to attack opponents.

Card stacking: Presenting only one side of an issue.

Glittering generalities: Using vague language to create a positive effect.

Political ads= Big Business

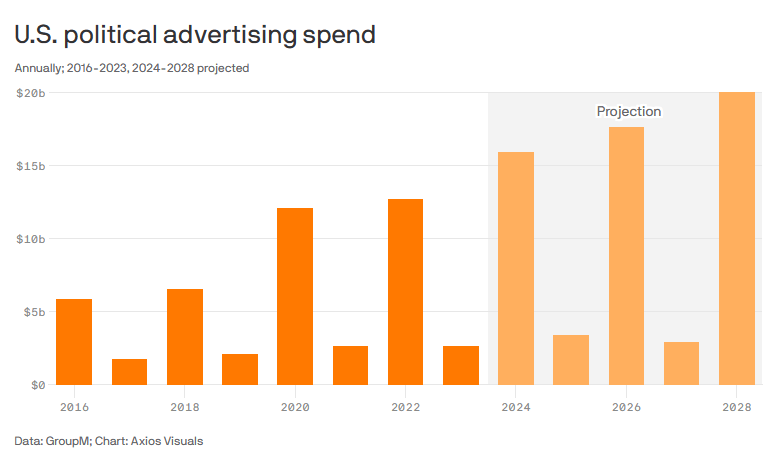

“According to GroupM, an estimated $16 billion in advertising is expected to be spent on political ad campaigns for the 2024 presidential election cycle.” (Source). That’s a lot of money!

Those ads will be seen (and heard) on TV, radio and of course the Internet. And because of something called “behavioral targeting”, those ads will be positioned and exposed to audiences that consultants have identified as important to sway. And with Smart TVs, ads can be directly transmitted to specific viewer’s homes. So, what YOU might see may not be what your neighbor sees.

Who Benefits?

This is a key media literacy question and concern. In my workshops, I always ask this question and typically no one comes up with the quintessential response. In fact, if I asked you WHO owns your local radio or TV station, you probably don’t know. Every quarter, large media owners must declare their profits. And during election years, they are laughing all the way to the bank. Why? Because THEY are the beneficiaries of all that campaign ad revenue.

Have your students look up Sinclair, Nexstar, Gray, Scripps and Extravision. (Tegna was recently acquired by Standard General.) Their websites reveal how many TV stations they own and where they are located.

What Does A 30 Second Ad Cost?

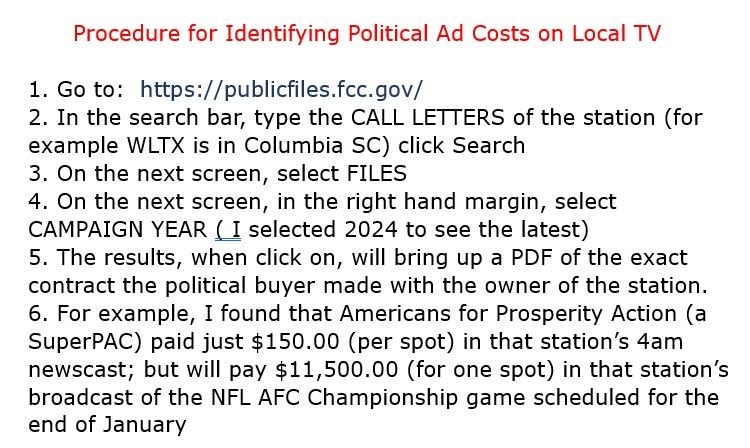

For years, I asked this question and discovered the answer is available on a webpage of the Federal Communications Commission, which requires TV stations to post contracts with the candidates. So here is the procedure:

Students can easily compare and contrast the cost of ads on different stations at different times of day and how much that might vary from one TV market to another.

Beware of Deepfakes

With Election 2024 right around the corner, it will be critically important for students to be able to determine if what they are seeing (and hearing) is authentic. Media analysts have warned that with the advent of AI software, it can be virtually impossible to know if what is on the screen represents reality. It may be helpful for educators to explore what is a DEEPFAKE and how easily images, words and sounds can be altered.

Take a look at this short video, produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Company. The US Federal Election Commission is monitoring social media and websites and promises to remove them.

If you want to know more, I recommend The Role of Media In Politics, the website I created as part of The Media Literacy Clearinghouse. See also, the blogs I contributed to Middleweb.com